Beware! Beware! Five Controversial Ideas

Here's my quintet of outrageous postulations, each one guaranteed to upset someone somewhere because that's what we do best.

Number One: Zeppo Marx is an integral component for Groucho Marx’s best film work.

When we think of the Marx Brothers, as I do on a daily basis, we think of the core trio Groucho, Harpo, and Chico. Zeppo gets written off as the asterisk. Nonsense. He’s more than just the handsome Marx brother dressed in a sharp suit. Zeppo has a tough job which he executes beautifully: the strong supporting straight man for his brother Groucho.

Without Zeppo, Groucho doesn't have the right person bounce off the best of his jokes and insults. Consider the scene in Animal Crackers (1930) when Groucho’s Captain Spaulding dictates a letter to his private secretary, Zeppo’s Jamison. It’s a marvelous sequence, building jokes that don’t always follow a linear progression. Zeppo’s sly responses, delivered with perfect timing, give Groucho exactly what is needed at required moment for maximum effect. It’s akin to a solid sparring partner willfully taking on the hard blows so the heavyweight champion can perform at his best. Here are the two masters at work:

Compare the Paramount Marx Brothers films to any of the post-Zeppo Marx Brothers movies. The subsequent replacements in the so-called “Zeppo role” can’t match their predecessor. Allan Jones is the Zeppo of A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937), but his real function is love interest to Maureen O’Sullivan. He’s an appendage to the Marxes rather than a partner. In Animal Crackers, those roles as played by Hal Thompson and Lillian Roth, are secondary. Their real function is to serve as breaks between comedy set pieces, plus keep the plot moving forward.

In that rare moment of Zeppo as love interest, opposite Thelma Todd in Horse Feathers (1932), the relationship is really a catalyst for subsequent gags. Zeppo has a job to do, one that becomes clear when Groucho also woos Todd, plus the closing wedding scene between Todd, Groucho, Chico, and Harpo. There was no need to turn Zeppo into the male half of a stock 1930s-era romantic movie couple.

Zeppo, bored with acting, left the team after Duck Soup (1933) and became a powerhouse Hollywood agent. He found another calling as a successful inventor with three patents, including one for the Marman clamp, which became a vital component for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The Marman clamp remains a standard for engines in today’s vehicles, ranging from your car to spaceships. But when Zeppo left movies, it became self-evident of his importance to Groucho. As the late, great comedian Gilbert Gottfried observed, A Night at the Opera was the beginning of the end for the Marxes. In addition to being the consummate aristocrat, Gilbert’s assessment was spot on. Without Zeppo, Groucho lost his straight man. In Opera and Races Allan Jones is just an amiable guy with a plotline that’s resolved with help from the Marxes. Compared to the cream cheese performance of Kenny Baker in At The Circus (1939), Jones is the best post-Zeppo Zeppo we’ve got. Fortunately Groucho still had the pompous talents of Sig Ruman to play with.

Don’t get me wrong: even sans Zeppo the Marx Brothers are far superior to most screen comedians of the 1930s and even into the 1940s. Yet there’s a reason that their first five films with Paramount are the team’s best work. Chalk that up to Zeppo’s brilliance.

Number Two: America’s Most Underrated Musical Genius: Tiny Tim.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: People were creeped out by Tiny Tim—his music, his appearance, his voice, his mannerism, his sartorial tastes. Fair enough. That said, I met Tiny a couple of times and can promise you, his onstage persona was no act. Tiny Tim onstage was the same as Tiny Tim offstage. I once had a discussion with one of his managers. (Short version: the guy wanted me to write The Tiny Tim Story. I declined.) The manager’s feeling was that Tiny was an autistic savant, blessed with astonishing musical gifts. I concurred.

We're told as kids that when we grow up we can be anything we want to be. That’s exactly what Tiny Tim did. I suspect that’s why he made so many people uncomfortable. He refused to conform to anyone else’s idea of normality. Tiny developed a signature look that kept for life: his trademark long hair, white pancake makeup, and garish jackets. He carried his beloved ukulele not in a fancy case but in a simple paper bag. Tiny lived in a world unlike anyone else’s and was forever trusting of agents and managers, which made him a perfect target for grifters. He earned millions for others and lost millions on his own. Tiny didn’t understand that people weren’t laughing with him but laughing at him; a naïve quality which was exploited for cheap laughs by Johnny Carson and Howard Stern (among others).

But to dismiss Tiny Tim as a show business oddity is to dismiss a long gone era of American popular music. Few people understood that Tiny Tim had a keen mind for his greatest love: the singers and songs of early 20th century Tin Pan Alley days. His idols were the now forgotten musical stars Henry Burr and Billy Murray, the Harry Styles and Ed Sheeran of the early 20th century. As a teenager Tiny (born Herbert Butros Khaury) spent countless hours in his bedroom listening the old recordings of Burr, Murray, and others. But it wasn’t just simple listening: he absorbed these singers and their songs. Through this intensive study Tiny developed a remarkable range as a singer. He could switch from a deep bass to high falsetto within the same lyric, a talent he used with remarkable clarity on Burr’s hit “The Old Front Porch.” His rich baritone tapped into the heart of George M. Cohan’s patriotic march “You’re a Grand Old Flag.”

Peers in the music industry loved Tiny Tim’s sincerity, his devotion to his music. Both John Lennon and Paul McCartney defended Tiny from flippant detractors. “It's like-- it's a funny joke at first,” McCartney told one interviewer. “But it's not, really. It's real and it's true." Lennon agreed, saying “He's the greatest ever, man! …We saw him. He’s real.”

Tiny's 1968 debut album God Bless Tiny Tim sold 200,000+ copies that year, with the single “Tip Toe Through the Tulips” peaking in June at #17 on the Billboard Chart. There’s a reason for that success. God Bless Tiny Tim is not a novelty record, as dismissed by some. Rather, it’s a carefully crafted album, produced by Richard Perry, the same Richard Perry who worked with other high caliber artists like Captain Beefheart, Harry Nilsson, Rod Stewart, Carly Simon, Ringo Starr, and Barbra Streisand. Think about that last one. Tiny Tim and Barbra Streisand had the same producer. Yes, I said “other high caliber artists” in a deliberate comparison.

The record opens with Tiny’s acapella version of the Jimmy Van Heusen & Jonny Burke song “Welcome to My Dream.” As channeled through Tiny’s reedy tenor the song becomes ethereal, an almost hallucinatory opening for what is to come over the next 15 tracks. It’s followed by Tiny’s signature “Tip Toe Through the Tulips,” sung in a lively falsetto while he accompanies himself on the ukulele. And that’s just the first three and a half minutes. The album is a kaleidoscope mixture of standards (including “Stay Down Here Where You Belong” by Irving Berlin, a song Berlin hated), and modern pop. One of the album’s highlights is Tiny’s duet with himself using both his falsetto and bass to sing the Sonny and Cher hit “I Got You, Babe.” His rendition of Gordon Alexander’s “Strawberry Tea” is a haunting addition to the late-1960s psychedelic music scene. McCartney and Lennon got it right when they called Tiny Tim “real and true.”

One of Tiny’s many admirers and occasional collaborator was future Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan. "A lot of people just think that he was a joke,” Dylan said after Tiny Tim died on November 30, 1996. “But I’ll tell ya, no one knew more about old music than Tiny Tim did. He studied it and he lived it. He knew all the songs that only existed as sheet music. When he passed away, we lost a national treasure.”

Number Three: Truman Capote got it right in his review of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

On the Road is looked on by many as an iconic book, one of the greatest novels to emerge from the 1950s Beat Generation writers. Include me out, thank you very much. After several false starts, I finally forced myself through On The Road cover to cover. Here’s the plot: a bunch of guys bum their way around the United States via their own cars, hitchhiking, and the occasional bus. They get drunk. They get laid. They philosophize and listen to some hepcat jazz. The characters are all stand-ins for Kerouac and his Beat Generations pals. The end.

Wow. What’s not to like in this self-indulgent junk masquerading as literature? I mean, besides everything?

The book was published in 1957. Five years later the John Ford Western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence added an oft-repeated phrase to our lexicon: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” That’s a good summation of On the Road’s backstory. The tale is often told how Kerouac taped together reams of tracing paper to create one long continuous roll. He fed that into his typewriter, channeled his inner voices, and voila! A masterpiece. Kerouac tapped into a brilliance that could only be done through marathon writing sessions with no breaks to put a new sheet of paper in the typewriter. Long before we wrote on computers using Google Docs or Microsoft Word, nonstop writing meant feeding one long roll of paper into your typewriter.

If you have the slightest understanding of how a typewriter works you'll quickly realize that an endless scroll of paper will curl up on it itself, turning into a tangle. Regardless, “The Scroll” (as Kerouac’s taped-up sheets are called) is treated like some kind of literary Torah. It’s exhibited under museum glass cases, bathed in soft lighting, and gazed upon with reverent awe by creative writing majors and other assorted hipsters. I’ve seen the thing myself. I was not impressed. It didn’t look like some holy text. No, it was just one long, messy first draft with no margins nor paragraph breaks on a single-spaced roll of paper. It was unreadable. No publisher in their right mind would have accepted it without severe revisions. Like any other wordsmith, Kerouac had to abide by the cardinal rule that good writing is rewriting.

But the tale of The Scroll grew into something mystical. Litterateurs turned the legend into fact. Within this long continuous stream of consciousness work, Kerouac was calling on a muse greater than himself, unleashing On The Road through an act of frenzied artistic creation.

In other words: print the legend.

The reality: Kerouac died a drunk who lived in his mother's basement. He was less inspired artist and more like an alcoholic Rupert Pupkin. Today he would have his own YouTube channel. Or maybe he’d just be churning out his own Substack.

Truman Capote's assessment of On the Road and Kerouac’s Scroll was concise and spot on: “That’s not writing. It’s typing.”

Indeed.

Number Four: Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot JFK.

Okay, this one flies in the face of every Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory expert, which is everyone on Twitter X. Questions about who really killed President Kennedy burst onto the scene through attorney and self-appointed sleuth Mark Lane and his 1966 blistering critique of the official government investigation: Rush to Judgment: A Critique of the Warren Commission's Inquiry into the Murders of President John F. Kennedy, Officer J.D. Tippit and Lee Harvey Oswald.

Lane published a few more books on the assassination, including Plausible Denial: Was The CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK? (1991). Spoiler alert: despite Lane’s purple prose and the Gordian knot of intergovernmental connections he ties together in the book, the correct answer to that subheading question is a hard “no.”

Lane’s theories became catalyst for several libraries’ worth of books and documentaries about the Kennedy assassination. “Who really killed JFK?” turned into a byzantine game of theoretical badminton with self-appointed experts batting around a conspiracy shuttlecock. How could the Warren Commission have gotten it so wrong? Everyone knew what really happened in Dallas on November 22, 1963. It was all so obvious. The Mafia pulled off the ultimate hit by whacking JFK as revenge for his brother Bobby’s crusade on organized crime. No, that’s wrong. The Kennedy assassination was set up by Fidel Castro in retaliation for the abortive Bay of Pigs operation and/or Kennedy becoming the world’s hero and Castro turning into ultimate villain during the Cuban Missile Crises. Wait a minute. Can’t you see that the CIA wanted to expand the Vietnam War, so they worked with LBJ to get rid of Kennedy? Only mob bosses could order up a Presidential hit. Or Castro and his backers in the Soviet Union had both means and methods. Certainly the CIA could put in teams of sharpshooters throughout Dealey Plaza. Or maybe it was a combination of all these theories…and more! Just what was the government hiding? Hmmmmmm……

Whatever the theory of the moment, no matter where ideas mix, match, and/or contradict each other, they all have a common denominator: Lee Harvey Oswald was set-up by (FILL IN THE BLANK) when he pulled the trigger on November 22, 1963.

Rubbish. Oswald did it all by himself. No one else.

Lee Harvey Oswald was a seriously disturbed individual. In and out of juvenile detention centers as a teenager. Court martialed twice while serving in the Marines. Defects to the Soviet Union and when that doesn't work out, returns to the United States. Joins something called “The Fair Play for Cuba Committee.” Hands out pro-Castro leaflets on the streets of New Orleans, which lands him an interview on local television. Buys a mail order rifle. Uses it on April 10, 1963 fire into the home of Major General Edwin Walker, a retired military man with ties to white supremacist groups and the John Birch Society. A bullet nicks Walker but it’s nothing serious. Walker doesn’t know who it did, albeit many people would have liked to see him dead (only after the Kennedy assassination does it become public knowledge that Oswald was the gunman).

Fall 1963. A few weeks before the assassination, Oswald shows up in Mexico, trying to get back to the Soviet Union and/or Cuba by appealing to their respective embassies. Goes back to United States. Gets a job at the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas, earning $1.25 an hour. You know what happens next.

We can argue all day about the Mafia and the CIA and Castro, but let's be honest: why would any of them turn to a loose cannon like Oswald to do their dirty work? Consider his CV. If you were a Mafia kingpin or a rogue government official, would you rely on someone like Lee Harvey Oswald to be the key cog of your well-oiled presidential assassination machine?

Yes, the Zapruder film shows Kennedy’s head snapping back, indicating he shot from the front. But there are sound medical reasons explaining how the same physical reaction could be the result of that bullet fired from Oswald’s sixth story window perch overlooking President Kennedy’s motorcade. As for Oswald’s claim of “I'm just a patsy?” The record shows that he was mentally unstable. Oswald would have said anything to anyone, no matter how outlandish, to save himself.

But what about Jack Ruby? The guy with Mob connections who killed Oswald. It’s so obvious that Mafia bosses sent Ruby to silence Oswald.

Really? First, Ruby was at best a guy who knew a few Mafia associates and certainly none of the kingpins. He ran a strip club in Dallas, a business that’s always attractive to mobsters. But that doesn’t mean he got the assignment to take out Oswald. So how did he get such easy access to the police station when Oswald was being transferred to another facility? Given Ruby’s business, it was inevitable that he also knew a lot of cops and they knew him. He was a familiar face about whom no one gave a second thought. Keep in mind, in 1963 there wasn’t the kind of multilayered precautions we use in 2023 to protect notorious criminal suspects, let alone a presidential assassin. All Ruby had to do was walk into the police station on November 24, work his way through the lax security, and do the deed. No mobsters, no government agents, no Cuban cigars.

Ruby was an impulsive man who loved JFK. He maintained to the end of his life that he shot Oswald to spare Jacqueline Kennedy the ordeal of a trial. There are also some indications that Ruby may have taken medication which clouded his rational thinking on the morning he shot Oswald.

Let’s face it: we want to believe in a JFK assassination theory, however convoluted those conspiracies may be. It’s almost like folklore. But sometimes the most obvious answer is the most obvious answer. Lee Harvey Oswald was a disturbed man with a gun and proven track record of erratic behavior. He wanted to be remembered for doing something in this world. And that’s what he got by killing President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

Don’t take my simple Substack post as the end word on the Kennedy assassination (and why should you?). There are better, more thoughtful resources. Consider Gerald Posner, author of the exhaustive and impeccably researched book, Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK. At 600+ pages and weighing in at 2.35 pounds, Posner’s well-received investigation offers considerable proof that Oswald and not a cabal killed Kennedy on November 22, 1963. Still don’t believe it? Try Vincent Bugliosi, the man who prosecuted Charles Manson. His even more exhaustive book Reclaiming History: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy clocks in at 1,648 pages, plus a CD-ROM with endnotes, documentation, and other resources. The book weighs 5.95 pounds. His argument that Oswald was the lone assassin is extensive and airtight.

If you still believe there was a massive conspiracy and coverup in the JFK assassination, here’s a list of just about every theory out there. I invite you to wade your way through the morass. And when you’re done, look at a list of definitions for the word “up.” Figure out which list is longer and which is controlled by the Mafia and/or the CIA and/or Fidel Castro (with maybe some assistance from the Soviet Union).

Oswald acted alone. Sorry not sorry to ruin a conspiracy theorist’s day.

Number Five: Edward D. Wood Jr. is a vastly underrated filmmaker who was ahead of his time.

Francois Truffaut, one cinema’s greatest directors, famously declared “I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between; I am not interested in all those films that do not pulse.”

Well, who could that describe any better than Edward D. Wood Jr., director of such one-of-a-kind films like Plan 9 From Outer Space and Glen or Glenda (AKA: I Changed My Sex).

Yes, Wood’s screenplays are hinged on ridiculous plots, silly dialog, and rife with terrible performances. His lower than low budgets don’t waste any money on special effects. The invading flying saucers of Plan 9 are pie tins hanging off fishing wire. The cast accidentally knocks over tombstones made of cardboard.

Most famous of all, the star of Plan 9 died before the 1957 production began. Wood shot some footage of his friend, the dope-sick Bela Lugosi, not sure what he would do with it other than to convince potential investors and other actors that a big star was attached to the project. Yes, Lugosi once was a star and is still remembered for his riveting portrayal in Dracula (1931), a performance that set the standard for how the character continues to be interpreted.

Lugosi died before production began. Wood came up with the ingenious idea of filming Lugosi’s remaining scenes with a double hiding behind a Dracula cape. His choice was Dr Tom Mason, a Los Angeles chiropractor of Wood’s acquaintance.

Sure, if you compare it to Dracula, Plan 9 From Outer Space is a “bad movie.” But the worst film ever made? Not even close. It’s over-the-top crazy, which is why audiences love it. The film is available on streaming services, YouTube, DVD and Blu-ray. You can even see it at real live movie theaters. Plan 9 From Outer Space is a perennial favorite on the midnight movie cult circuit.

I maintain that worst movies ever made are movies that bore the audience. Right at the top of my personal list of boring bad movies is Steven Spielberg’s A.I. (2001). Millions of more dollars are wasted on every shot in that film than all the money in the entire Plan 9 budget. A.I. left me wanting to lob heavy rocks at the screen when boy robot David (Haley Joel Osment) pleaded ad nauseum “Please, Blue Fairy, please make me into a real live boy.” Compare that to the dialog in Plan 9 From Outer Space. What’s not to enjoy when Criswell, a charlatan TV psychic cast as the film’s narrator, delivers great lines like “Greetings, my friend. We are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives!”

Now consider Wood’s earlier film Glen or Glenda, released in 1953. With Glen or Glenda Wood takes a deep dive into the underground world of gender outlaws living on the fringe of polite society. In addition to writing and directing the film, Wood plays the title characters of “Glen” who only feels his true self when he’s dolled up as his alter ego “Glenda.” In that sense, the film is autobiographical. Wood himself was a “crossdresser,” the common term in 1953 for men who preferred to wear women’s clothing. Another Glen or Glenda plot line follows the story of Alan, a WWII veteran who undergoes what was known in 1953 as a “sex change” operation. Alan is transformed into Anne, the woman she always knew herself to be, even when fighting on the front lines in Europe.

Today we’re in a world where transgender people are legally denied the right to medical care and basic public accommodations. Transgender men and women are derided on Fox News and by elected officials at all levels of government. These are the same issues Wood tackled in 1953. Gender dysphoria was mocked then and is mocked now. Wood has enormous compassion for his characters. The film’s plea for tolerance and acceptance offers lessons we still need to learn some seven decades after Glen or Glenda was first released.

Lugosi, narrator of Glenn or Glenda, gives a weird and wonderful performance. His scenes don’t fit well with the rest of the film, but they provide Wood an artistic opportunity to strut his surrealist stuff. The film opens on mad scientist Lugosi, ensconced in a lair full of skulls, cobwebs, and beakers emitting mysterious fumes. Stock footage of a buffalo stampede is superimposed as Lugosi intones “No one can really tell the story. Mistakes are made. But there is no mistaking the thoughts in a man's mind. The story is begun.” At points he delivers his lines with all the seriousness of Shakespearean actor playing Richard III or the maddened King Lear. “Beware! Beware! Beware of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep. He eats little boys, puppy dog tails and big, fat snails. Beware. Take care. Beware.” It’s bizarre, yet beautiful.

The list of filmmakers whose works are considered a genre all their own is an elite club. Dorothy Arzner. Ingmar Berman. Robert Bresson. Jane Campion. John Cassavetes. Federico Fellini. John Ford. Alfred Hitchcock. Stanley Kubrick. Akira Kurosawa. Spike Lee. Ernst Lubitsch. David Lynch. Vincente Minnelli. Martin Scorsese. Quentin Tarantino. Agnes Varda. Lois Weber. Truffaut himself. Add to that list the unparalleled work of Edward D. Wood Jr., a man whose films express both the joy and the agony of making cinema.

One more bonus controversy: Why Women Are Superior to Men.

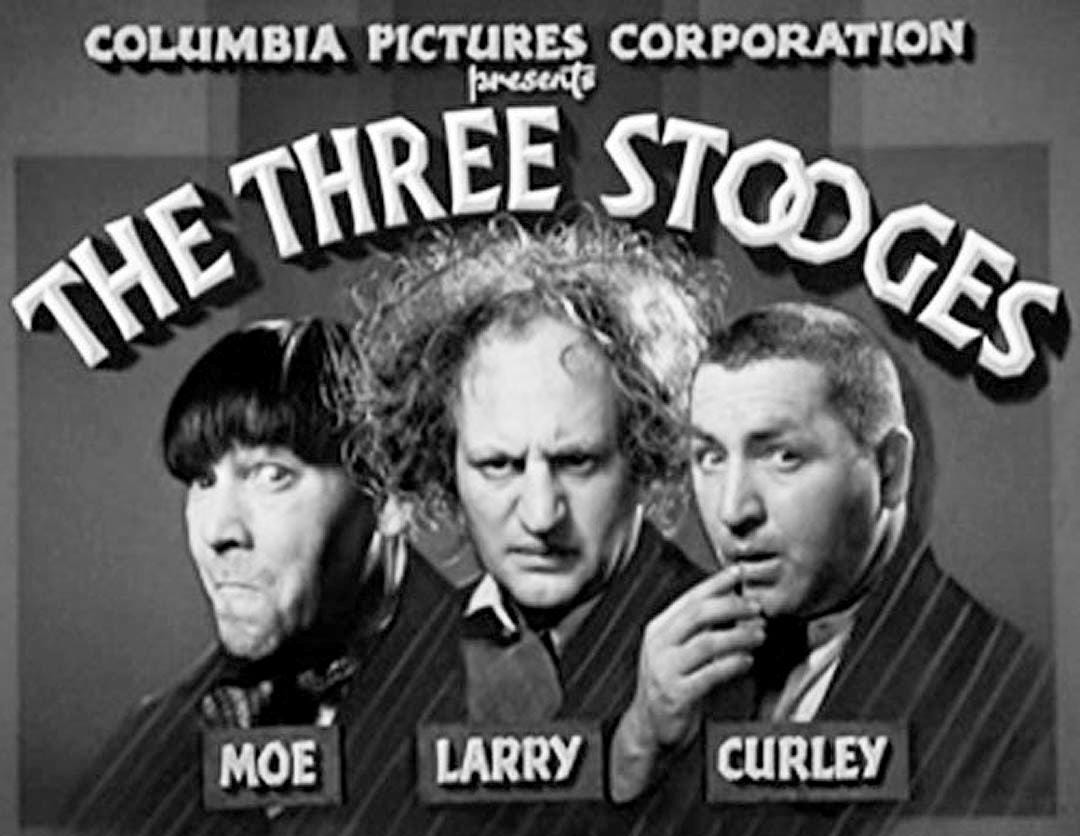

Women are superior to men as the vast majority of women don't think The Three Stooges are funny. Neither do I. This, of course, makes me a superior man. Full stop.

Scream about my controversies in the comment section or on my Twitter X @realarnieb. Check out the related links below. And please visit my website www.arniebernstein.com.

Fun and interesting reading for an lovely day on my back deck!!! Thanks!!!