Cutting "The French Connection"

A classic of American cinema loses nine seconds. Who cares? A lot of people, that's who.

August 7, 2023 Addendum and Adieu: This was originally published on June 27, 2023. As I pointed out below, director of The French Connection William Friedkin gave no public statement on this controversial censorship of his greatest film. Within the past hour, it’s been announced that Friedkin passed away on Monday, August 6. One obituary stated that Friedkin had suffered from various health issues these past few years, which may explain his silence. Regardless, the film should be restored to its original cut, and now in the memory of its great director.

When I was 12 there was nothing better than Mad Magazine for sheer irreverence. Mostly I loved the film parodies. In July 1972 they published What's the Connection?, their take on the 1971 film The French Connection. I don't remember much about the Mad version, other than it ignited my lifelong passion for the real movie.

I was only in seventh grade but I had to see The French Connection. There was a major obstacle to this goal: the film rated R by the MPAA meaning “under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian.” When it played at the neighborhood theater I begged my parents to take me to see it. The incessant pleadings went unfulfilled. I got a hard “no” every time. Mom and Dad didn't think I was ready for this kind of movie, certainly not as a twelve-year-old kid. It was an era were movie ratings actually meant something.

Since the film was forbidden, I did the next best thing. I got my hands on a copy of the book the film was based on: The French Connection: The World’s Most Crucial Narcotics Investigation by Robin Moore. I pored over it incessantly, reading and rereading The French Connection like it was a holy text. The real-life story of New York narcotics detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso was a whole lot better than the usual junior high crap I had to read for seventh grade book reports. I’ve hung on to that copy of Moore’s book over the years, the pages yellowed and cover torn. It’s a totem of my real education.

When I finally saw The French Connection I was 16, still a year under the age of consent. It was was broadcast on network television five years after its theatrical release, now cut up and packed with commercials. It didn't matter. I watched The French Connection on my little black and white TV, taking in every moment. It was truncated but still everything I hoped it would be.

Though film is mostly fictionalized, it gave smart insight into the world of New York police work in the late 1960s/early 1970s. Gene Hackman stars as New York police detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, with Roy Scheider as his partner Buddy “Cloudy” Russo. It’s filmed in documentary style with shaky camera work, stolen shots filmed without a permit, and the iconic chase scene as Popeye drives like hellfire through Brooklyn, trying to keep up with an elevated train that’s been hijacked. The film won multiple Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director for William Friedkin, Best Film Editing by Gerald B. Greenberg, and Best Adapted Screenplay by Ernest Tidyman (see my postscript for more on Tidyman). Hackman took home the Academy Award for Best Actor. For those of you unfamiliar with The French Connection, here’s a quick overview.)

I've since seen The French Connection many times over, sometimes on a theater screen the way it was meant to be seen, and on cable television. I have the two-disc DVD set, brimming with extras like the director’s commentary by Friedkin, deleted scenes, and a documentary about the film produced by BBC television. When the digital edition of The French Connection came out a few months ago, I downloaded it to my iPad.

I wish I hadn't. What Apple and other digital platforms sold wasn’t The French Connection.

What’s Changed?

There's a key scene, about ten minutes into the film where we get fierce insight into Popeye's psychology. It’s right after Popeye, dressed as Santa Claus, has arrested a drug dealer. “Arrested” is too gentle a word: Popeye and Cloudy brutalize the man. They slap him around, while Popeye screams in the dealer’s face “Did you ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?” It’s Popeye’s verbal tactic to throw off the criminal, confuse him, try and get him under control. Before the mayhem begins, the arrestee whips out a knife, cutting Cloudy in the forearm.

Back at the police station, Popeye and Cloudy have a brief exchange. Here it is verbatim in the original script, one word obscured. You can figure out what that word is:

It's shocking to hear The Word come out of Popeye's mouth. He is ugly, crude, and a unapologetic racist. But that's the point. There's no mistaking that racism is part of what motivates Popeye. In a later scene he takes a perverse joy in raiding a bar with Black clientele. It’s who he is.

Roger Ebert, in a consideration written a few years after the film’s original release, wrote: “(Popeye) Doyle himself is a bad cop, by ordinary standards; he harasses and brutalizes people, he is a racist…” The character is, Ebert points out, is “an amoral hero.” Ebert’s peer Pauline Kael also zeroed in on Popeye’s racism, “(He) is insanely callous, a shrewd bully who enjoys terrorizing black junkies,” she wrote, adding that the character is “a subhuman son of a bitch.” (Unlike Ebert, who praised the film, Kael hated it for the same reasons Ebert loved it.)

The exchange, complete with the racial slur, is essential to understand Popeye and the world he lives in. When The French Connection was first released, African American audiences were among its biggest fans. In the documentary A Decade Under the Influence, a great film about 1970s films and filmmakers, Roy Scheider talks about watching the film with a largely Black audience. He was shocked that they broke out into applause when Popeye abuses African American suspects, as well as the use of The Word. Upon further reflection, Scheider explained, he understood why these people were cheering. For the first time, a movie dared to show the brutality African Americans experienced in 1971 at the whim of racist white cops—something still commonplace some five decades later.

The Word and Its Use

I have no problem with swearing. My vocabulary can be quite peppery when I’m on a good tear. But I draw the line at The Word. It curdles my stomach. There's something about hard consonants, like those at the center of The Word, that drive home the hatred behind any racial or religious slur. Oprah Winfrey gave a definitive commentary on The Word and why she will never use it when she told an interviewer, “I always think of the millions of people who heard that as their last word as they were hanging from a tree.”

That said, I don't have a problem with The Word being used in books, plays, or films like The French Connection. It provides insight into characters and the worlds they inhabit, exposing their hatreds while making a larger comment on society. Two American classics of different times and different centuries—Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) and Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)—use The Word with an effect that sets off sparks like a hot iron being hammered on an anvil. In both cases it’s upsetting, as it should be, just as it is with The French Connection. Racist characters use racist language. Using The Word underscores the hatred permeating the real story of America.

The French Connection is a cinematic classic. In 2005 it was named to the National Film Registry of Library of Congress. The Film Registry was founded with the aim of “ensuring that motion pictures survive as an art form and a record of our times.” Other films joining The French Connection on the 2005 honorees include such Black-themed movies as Hoop Dreams (1994), Jeffries-Johnson World's Championship Boxing Contest (1910), A Raisin in the Sun (1961), and A Time For Burning (1966). James H. Billington, head of the Library of Congress at the time, stated "By preserving American films, we safeguard a significant element of American creativity and our cultural history for the enjoyment and education of future generations.”

Disney had other ideas.

In 2019, The Walt Disney Company bought all the film and television assets of 21st Century Fox: in essence the output of one of America’s great production studios. For a mind-blowing price of 71.3 billion dollars, Disney now owned everything from the Home Alone, Alien and Star Wars franchises, to Marvel Universe movies, to long-running television shows like The Simpsons. Also among Disney’s new properties: The French Connection. And at some point somewhere within the Disney world, its Corporate Powers That Be deemed that the exchange between Popeye and Cloudy be trimmed of The Word.

As it now plays, the scene opens with Cloudy lumbering into the precinct foyer, his coat draped around him, covering his bloody arm. He is in the background of the shot. Suddenly there’s a jump in the action. In the same shot Cloudy is now bantering with Popeye at the precinct exit. It’s an awkward cut within the scene that no editor worth his talents would stand for. Anyone seeing The French Connection for the first time might be shocked to learn it won the Oscar for Best Editing. The natural rhythms of the scene, complete with the ugly language that takes us deep into Popeye’s mind, is eviscerated.

Not Just Disney

As expected, fan outrage over the cut is roaring throughout the Internet via film blogs and social media posts. I have yet to see anyone defend The Word or unbridled use it. At the center of The French Connection is a racist cop. Why wouldn’t he use The Word in his everyday vernacular? Popeye’s inherent racism is never portrayed as admirable. It is part of who he is, another layer of the boiling emotions he brings to the job. Popeye is pissed having to arrest small-time dope dealers. Stumbling on a connection between wealthy French heroin smugglers and American mobsters is Popeye’s career builder.

To make matters worse, The Criterion Channel has joined Apple and other digital platforms by streaming only the butchered version of The French Connection. Film fanatics like me love Criterion. Its Blu-ray/DVD offerings—The Criterion Collection—are an eclectic mix of great cinema, from silent era through modern day films, popular movies and obscure cult items, and sharp-edged work by established Hollywood directors, indie outsiders, and foreign filmmakers. As stated on the Criterion website:

As of this writing (June 27, 2023) Criterion hasn’t said a word about the controversy. So much for Criterion maintaining “its pioneering commitment to presenting each film as its maker would want it seen…”

It’s not just Criterion’s corporate hypocrisies that bothers film fans. What’s just as bad—if not worse—is the silence from the most passionate of all film scholars: Martin Scorsese. Scorsese isn't just America’s premier director. He’s a zealous advocate for teaching film history. Scorsese’s nonprofit organization The Film Foundation is dedicated to preserving classic cinema, restoring films that might otherwise have disappeared due to aging negatives, lost footage, or other factors. The Film Foundation’s mission statement reads much like Criterion’s:

Consider some of the films Scorsese has rescued from complete deterioration. There are the early silent films, old newsreel footage, and obscure experimental films that you’d expect. Then there’s the many surprises, the big name films we take for granted as part of our cultural landscape. All That Jazz (1979), Giant (1956), King Kong (1933), The Misfits(1961), My Little Chickadee (1940) Night of the Living Dead (1968), On The Waterfront (1954), Rashomon (1950), the luminous The Red Shoes (1948), and A Woman Under The Influence (1974), among many others. Six films by Charlie Chaplin, eight by Alfred Hitchcock, twelve by John Ford. Even Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982) is on the list.

Just last week Scorsese, along with Steven Spielberg, and Wes Anderson, released a statement on the potential changes to Turner Classic Movies (TCM) in the wake Warner Brothers corporate executives firing much of the TCM leadership. “Turner Classic Movies has always been more than just a channel,” they said. “It is truly a precious resource of cinema, open 24 hours a day seven days a week.”

Silence

It's not like Scorsese is a stranger to The Word. It does some heavy lifting in his films like Mean Streets (1973), Raging Bull (1980), and Goodfellas (1990). Scorsese himself spits out the word several times in Taxi Driver during his cameo appearance as a psychopathic husband who wants to shoot his wife after he learns she’s having affair with an African American man. Keep in mind, Taxi Driver was made just five years after The French Connection.

Given his passion for film preservation, given that The French Connection is a forerunner to his own films with its gritty portrayal of New York street life, Scorsese’s silence on the issue is demoralizing. A classic by one of his peers has been altered. Never mind Scorsese the Director. Where is Scorsese the Film Preservationist?

Paul Schrader, Scorsese’s sometimes collaborator, is another notable voice that is muted on the issue. Schrader collaborated with Scorsese as screenwriter on several films, including Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Bringing Out The Dead (1999). As a writer-director himself, Schrader has used The Word extensively in his films, such as Blue Collar (1978) and Hardcore (1979). Schrader has been criticized for the coarse, often racist language of his characters. But he’s not one to suffer film fools lightly. Schrader’s unfiltered diatribes set off considerable discussion on his Facebook page.

And yet Schrader is another big name who has said nothing about The French Connection butchery. On a chance that he might respond, I posted on his Facebook feed, asking Schrader for his thoughts on the cut. His answer was disappointing, both in content as well as Schrader’s seeming unwillingness to expound on the issue.

I did a google search based on Schrader’s comments. Nothing turned up. Perhaps he spoke with Friedkin; given their status as elder statesmen of 1970s New Hollywood directors, it stands to reason they know each other. As of this writing (June 27, 2023), Friedkin has made no public statement. Yet in light of the importance of The French Connection to American cinema—as well as Friedkin’s career—you’d think he’d have an opinion one way or other. Instead, we’re stuck with Schrader’s cryptic and unsubstantiated Facebook post.

Words matter. It's not The Word that is obscene, but rather its use. I can't imagine anyone other than a virulent racist enjoying Popeye’s pointed use of The Word. Anyone who finds delight in the line doesn't need The French Connection to shove them over the edge into virulent racism. They're already there.

My parents were right not taking me to The French Connection. At age twelve I just wasn’t ready for the film. Today I have a better understanding of things that would have confused and upset me as a seventh grader. But as an adult, this nine-second cut by self-appointed censors is once again treating me—and every other viewer—as a child all over again.

We get it. We can take it. Restore The French Connection

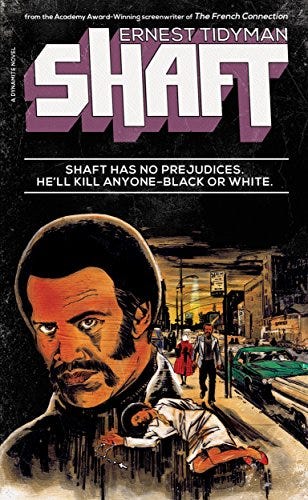

Postscript: Screenwriter for The French Connection is Ernest Tidyman, a white American writer of Hungarian-British parentage. After The French Connection, Tidyman’s best-known work is his character John Shaft, a supercool super-sexy African American detective. Tidyman wrote several Shaft novels, plus adapted a couple of the books for the movies. As played by Richard Roundtree, John Shaft was an iconic figure in low-budget blaxploitation films of the1970s. Or as Isaac Hayes crooned in his Oscar-winning theme song for the original 1971 Shaft film adaptation: “who’s the black private dick that’s a sex machine to all the chicks?” Tidyman’s work on the Shaft books and then the first film led to him being hiring as screenwriter for The French Connection. This strange irony makes Popeye’s dialog cut all the more ridiculous.

What are your thoughts about the issues discussed here? Share your ideas in the comment section or on my Twitter @realarnieb. And check out my website www.arniebernstein.com.

Related Links

IMDB Page for The French Connection

Shooting script for The French Connection