Grandma Lena and Me

The 400 Theater, a legendary Chicago movie house, may be closing. The news brought back memories I wasn't expecting.

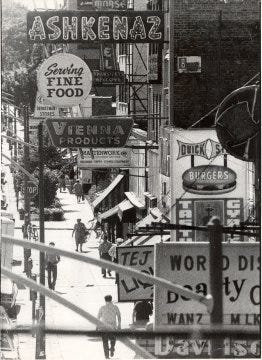

When I was in high school million years ago in the 1970s, I spent countless weekends staying with my Grandma Lena at her apartment on the corner of Morse Avenue and Sheridan Road, in Chicago’s East Rogers Park neighborhood.

Grandma Lena, my mom's mom, was born Zendahl Bornstein on August 3, 1907 in Częstochowa, Poland. She immigrated to America with her family via S.S Amerika, arriving at Ellis Island on July 2, 1913, a month shy of her sixth birthday (the ship’s manifest mistakenly lists her as seven years old). There is some confusion on the family name. The manifest lists the surname as “Bornstein.” But other official documents I’ve seen on the Ancestry website state her maiden name as “Bernstein.”

Regardless, she married my grandfather Leo Jacobson in the late 1920s (I don’t know the exact date or year). My mom Sheila Jacobson was born in 1933 and married my dad Eugene Bernstein in 1955, thus bringing the Bernstein name back to the fold. Dad’s Bernstein surname was from his father Samuel who was born in a little shtetl outside of Kyiv, which was then under control of Tzarist Russia (the more things change....). In case you’re wondering, no, my parents’ marriage was not a case of distant cousins getting hitched. Bernstein is a common name, the Ashkenazi Jewish equivalent of Smith or Garcia. There’s a whole lot of us.

Grandma Lena looked out for me from my earliest days. When I was just five months old, she guaranteed I would grow up as a leftist. At the time my parents and I lived in Park Forest, a suburb just south of Chicago, where Grandpa Leo served as a village trustee. One October afternoon, Grandma loaded me up in my baby buggy to take me out for a nice walk. We were back at the house in less than half an hour. My mother, surprised that our walk came to a quick end, asked “Why did you bring him back so soon?”

It was late October of 1960. The presidential race between Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John F. Kennedy, already tight, was growing tighter. Nixon was in Park Forest that day, delivering a campaign speech (which can read here, October 29, 1960). When she saw the growing crowds waiting for Nixon to speak, Grandma Lena reversed course and took me back home.

Why did she bring me back so soon? Grandma Lena’s answer was short and to the point. “I didn't want him exposed to that shit,” she said, voice seething with contempt. You could say “shit” in front of Grandma Lena all you wanted, but if you said “Nixon”, she would turn her head. From her perspective, the name of that detestable Jew-hater Nixon was the real obscenity.

Our Jewish liberal bond was set. Other bonds would come. Grandma Lena and I were in synch, some in ways that I am just beginning to understand.

After Grandpa Leo died in 1969, Grandma Lena moved to the Rogers Park apartment. During my freshman year of high school, Mom and Dad agreed that I was old enough to take public transit into the city, weekend bag in hand, and keep Grandma Lena company. My Fridays through Sundays with her were an absolute joy. I was a high school oddball, living in a suburb where being a high school oddball wasn’t a good option. Grandma Lena’s apartment was my getaway relief. It was a place where I could be the person I knew I was by someone who understood me. When I was with Grandma Lena, my adolescent awkwardness disappeared.

Together Grandma Lena and I watched the Watergate hearings on TV, rooting for Senator Sam Ervin and booing the obvious offscreen villain. Her contempt for Nixon never swayed. I once shared a poem with her. It went like this:

I’m glad I am American.

I’m glad that I am free.

But I wish I was a little dog,

And Nixon was the tree.

Of course she loved it. It was better than anything that could have been composed by lesser talents like those Jew-hating hacks T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound.

Grandma Lena was from a generation where everyone smoked; she sucked on her Pall Mall cigarettes as if they were a lifeforce. Me, I grew up on antismoking campaigns. More than once I hid her cigarettes in the name of good health. Hers, not mine. Grandma Lena wanted to kill me every time I came between her and Pall Malls.

Like I said, she was a strongly opinionated woman and wasn’t shy about letting you know what she was thinking, including things that today we’d call “cringy.” Grandma Lena wasn’t a racist per se, but she had her prejudices, those preconceived notions that plagued her generation. I took great delight in lampooning her over this. Once, when we were watching Sammy Davis Jr. was on TV, I said, "Look, Grandma! He's Jewish, just like us." She didn’t say anything. She didn’t have to: the look she shot me said it all.

Despite her character flaws, Grandma Lena was incredibly funny. She had a quick and caustic wit, steeped in Borsht Belt-style humor. Part of the reason I love the movie Blazing Saddles so much is because the Indian chief played by Mel Brooks uses Grandma Lena’s same jokey Yiddishisms.

There was a used bookstore on Morse Avenue, a couple of blocks from her apartment, where I spent hours on end. I couldn't get into AP English classes. The powers that be at my high school felt that I was ill-equipped for that level. My reaction was simple: fuck ‘em. I knew I was smart. You never saw me without a book in hand or pounding away on a typewriter writing a short story. The Morse Avenue bookstore became my AP English class. I found stuff there that was allegedly beyond my comprehension level, books that weren’t on any official reading lists but captured my imagination. They inspired me. As I write this I’m looking at my copy of Norman Mailer’s Of a Fire on the Moon, a book I bought at the Morse Avenue store. I’ve dived into Mailer’s meditation on the Apollo 11 moonshot many times over since the day I found it on the bookstore shelves. Its gray paperback cover is tattered, held together with decades’ worth of Scotch tape. It is a thing of beauty.

Best of all, Grandma Lena’s neighborhood was anchored by The 400, a somewhat shabby movie theater that first opened in 1912 as a vaudeville stage. During the 1970s The 400 was home to eclectic bookings, and in all the best ways possible. It alternated first-run movies with foreign films, art house hits, revivals, cult classics, and movies people never heard of before watching them at The 400 nor any time afterwards. Within the course of a few months you could see Chloe in the Afternoon, Harold and Maude, The African Queen, Panic in Needle Park, and Los Olvidados. One double feature paired the 1975 supernatural thriller The Reincarnation of Peter Proud with Spirits of the Dead, an 1968 adaption of three Edgar Allen Poe stories directed by Federico Fellini, Louis Malle, and Roger Vadim. You get the idea.

Grandma Lena was insistent that I watch good movies. One weekend she told me to go The 400 to see a new movie called The Sting. She said I would enjoy it. I did. Another time she sent me to a double feature revival of The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. It was love at first sight. I’ve since devoured both films countless times. The Godfather holds a place of great esteem my personal movie canon. It seems like I find some new subtlety with every viewing. Hell, I can recite whole scenes verbatim on request. (I also find merits in The Godfather III, and don’t argue with me on that.)

But nothing quite measures up to my Godfather obsession as does the revelation I had at my first viewing. At the time my sophomore English class was immersed in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. We had the damnedest time getting through it. All that iambic pentameter and hierarchy of thanes were confusing. Reading the play out loud in class was even worse. We sounded like what we were: a bunch of 15 year old kids who had no idea what we were saying.

That all changed for me on that fateful afternoon at The 400. After 6 hours and 17 minutes of Godfathers I and II (plus a few minutes of intermission between films) Macbeth finally made sense. The plot and character elements were the same. A decent son of his beloved father figure is seduced by criminal power. He becomes a ruthless and strategic murderer. Add to that the stylized language and corruptions of the soul. Michael Corleone was Macbeth and Macbeth was Michael Corleone.

Shakespeare didn’t write a play: he wrote a 17th century first draft of The Godfather. I was self-impressed by my insight. Even my teacher thought I was onto something after I breathlessly explained to him my comparison of William Shakespeare to Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo.

I was hooked. “A film by____” in the credits had new meaning. I no longer looked at movies as mere entertainment. Let the other kids scream their way through Jaws, a silly waste of time I found dull and predictable (I still hold that opinion.). I wanted something else. I wanted to be challenged. I wanted more of what I watched at The 400.

Grandma Lena must have seen that spark in me. One weekend she was absolutely insistent that I go to The 400 to see something called 3 Women. Forget Jaws or Star Wars. When Grandma Lena said, “go see 3 Women,” she meant “go see 3 Women and see it now!” She was right. I was enthralled from the word go. The surreal relationship between Shelley Duvall and Sissy Spacek, as conjured through director Robert Altman’s stylistic vision was magical, a sophisticated head trip for a nerdy 17-year-old. Altman’s dream structure took me into a new cinematic realm, something way beyond Rocky or Grease.

I’ve often been tempted to watch 3 Women again but never will. I want to hold on to the magic of that original experience, a crystalized moment filtered through Grandma Lena’s understanding of me.

I started college the next year. I took lots of film classes and went to movies almost every day, sometimes two or three times if possible. I soaked in as much as I could: silent-era Soviet films, French nouvelle vague works, documentaries, short films, adult-themed animation, works by directors I grew to love like Welles, Wilder, Scorsese, DePalma, Kubrick, Truffaut, and of course Altman, plus a lot of off-beat low budget movies from directors no one knew nor ever heard from again. Grandma Lena’s influence held fast.

When I came home for winter break, we went to lunch at some cheap local diner. I went on and on about my classes and the movies I was watching. I don’t remember much of the conversation, but I’m sure it was the usual pretentious blatherings of any 18-year-old cineaste. It didn’t matter. What I remember most about that lunch was the smile on Grandma Lena’s face and the joy in her eyes.

She died not quite a year later, on September 29, 1979. I cried for days on end. I remember the last time I talked to her, right before I left for school in August. “I'll see you at Thanksgiving, Grandma,” I said. “I hope so,” was her response. I was in denial of how sick was—and how sick she had been for some time now. Grandma Lena was closing in on death but didn't want me to know. Even in her last days she was looking out for me.

Today, as I grow closer Grandma Lena’s age during the time we spent together, I’m learning about our final bond. Just as Grandma Lena saw in me things I couldn’t see myself, I see in her the most important thing we shared, something beyond our mutual Nixon loathing and movie love. In Grandma Lena’s lifetime it wasn’t something people talked about, other than in shameful whispers.

The two of us share the illness of depression. I have a strange gratitude to our disease. It draws me closer to my her. Nearly 44 years after her death Grandma Lena and I remain in synch.

More on that next week.

What are your memories of loved ones now gone and their lasting influence? Share them in the comment section or on Twitter @RealArnieB. And be sure to check out my webpage: www.arniebernstein.com.

Fantastic piece Arnie. That's my neighborhood.

I hope this is an early chapter in your memoir. Wonderful writing, Arnie.