Kurt Vonnegut on Writing with Style

Seven rules (plus one) I live by in every writing session. You should as well. And so on.

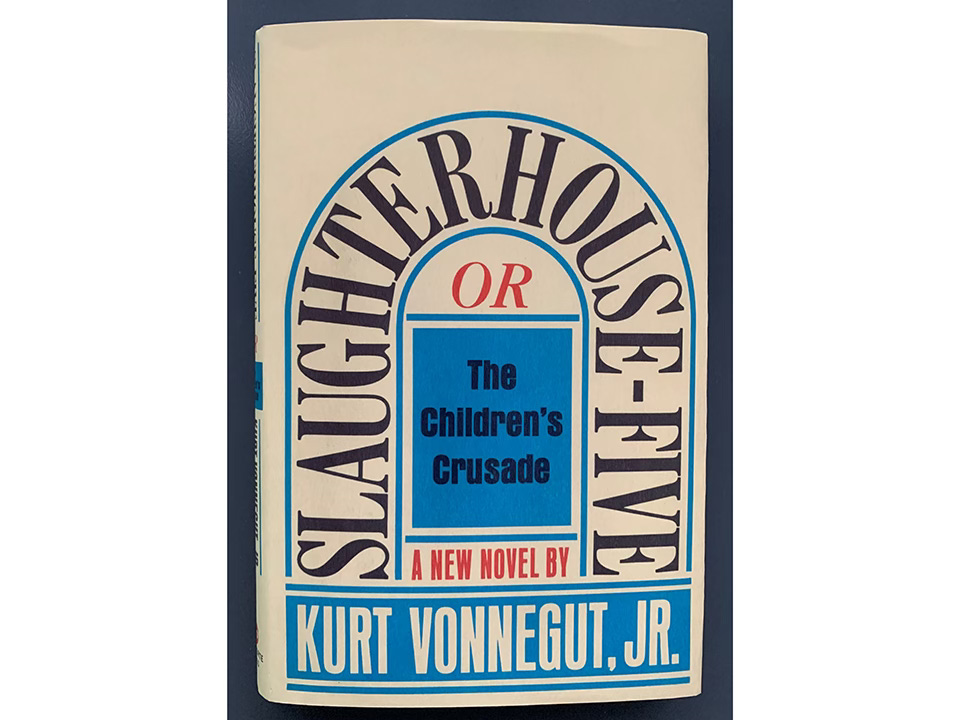

When I was fifteen, a family friend gave me a copy of the Kurt Vonnegut novel Slaughterhouse-Five or The Children’s Crusade, A Duty-Dance With Death (first published in 1969). He said I’d like it, but suggested that I skip the first chapter and start with Chapter Two. About a year later, when Slaughterhouse-Five was assigned for my junior year Contemporary Lit class, our teacher gave the same advice. I’m glad I ignored both of them. Not that I thought they were terrible people (they weren’t), but something bugged me about their mutual suggestion. Besides, if you tell me not to read something I’ll read it—true then, true now. Slaugherhouse-Five isn’t the same without Vonnugut’s prologue of Chapter One. The autobiographical introduction is vital to understanding what is to follow. That, plus it’s damn good writing.

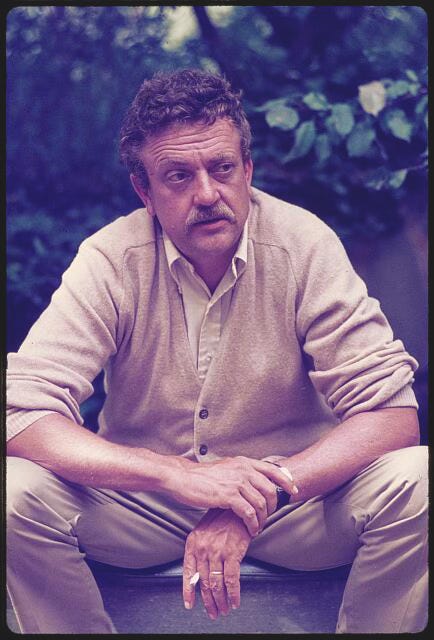

I’ll spare you my critical thoughts on Slaughterhouse-Five. You’ll find better elsewhere. Suffice to say, after reading Slaughterhouse-Five I fell in love with both book and writer. I snarfed up everything Vonnegut wrote. Breakfast of Champions. Player Piano. Mother Night. Cat’s Cradle. Welcome To the Monkey House. Slapstick. And so many more. The thing about Vonnegut is that once you start reading his books, it becomes addictive. You have to have another fix. At least that was the case for me, both in high school and all these years later.

I reread Slaughterhouse-Five at least once a year, and I’m always finding something new in its pages that I never noticed before. It’s a slim book, about 49,560 words, well below the average novel length of 60,000 to 80,000-plus words. Chapters are short. There aren’t many elongated scenes. A lot of the action is broken up into a few paragraphs with an extra space between movements. There are repeated phrases, like “so it goes” following any death within the book, from human demise to flattened bubbles in a pop bottle. Fiction intermingles with real events. Vonnegut tells you at the beginning what the last sentence will be. He messes with timeframes. The book vaults between a WWII story and scifi interplanetery travel. Vonnegut is a character himself, stirring his scarred memories as POW of the Germans into the mix. He brings in a character from a previous novel Mother Night. Slaughterhouse-Five is a dream of a book, with a narrative driven by deceptive stream-of-consciousness asides and the occasional smutty joke.

Here's the thing about Vonnegut. Whenever I indulge in a KV binge—both past years and present day—I find myself writing like him. Not that I’m banging out anything worthy of a bleacher seat in Vonnegut’s ballpark. I ain’t nowhere close to being that competent. Rather, I absorb what I most admire about his work: simplicity of style that belies its depth. Any writer would do well by studying the Vonnegut canon.

In 1980, International Paper—a paper manufacturer, as if you couldn’t guess—created a dynamic ad campaign: “We Believe in the Power of the Printed Word.” Well-known figures from literature and other arts provided their insights on various aspects of writing, culled together in an engaging series of magazine ad layouts. “Today, the printed word is more vital than ever,” read the copy. “Now there is more need than ever before for all of us to read better, write better, and communicate better. International Paper offers this new series in the hope that, even in a small way, we can help.”

Authors and other notables contributed their thoughts into a genuine potpourri of experts and topics: Malcolm Forbes on how to write a business letter. James A. Michener on how to use a library. John Irving on how to spell. Walter Cronkite on how to read a newspaper (remember those?). Steve Allen on how to read the classics. Also, “How to Read Fast” by Bill Cosby. That’s one to either read fast or skip entirely.

One source claims all the entries were ghostwritten by Billings S. Fuess, the Ogilvy ad man who conceived the series. I’m less inclined to believe this, given the caliber of the talent involved, although it is probable in a few cases. And I’m sure Fuess had a hand in the editorial process, given that he oversaw the ad campaign.

Vonnegut’s contribution was definitely not written by Fuess. “How to Write with Style” is pure Vonnegut. It has all of his trademarks: a strong use of his author’s voice, insightful jokes, coy wordplay. It’s straightforward, easy to read, and filled with good philosophical insight on the craft. Vonnegut’s seven rules (plus one) are a virtuoso’s guidelines for effective writing.

How to Write With Style

by Kurt Vonnegut

Newspaper reporters and technical writers are trained to reveal almost nothing about themselves in their writings. This makes them freaks in the world of writers, since almost all of the other ink-stained wretches in that world reveal a lot about themselves to readers. We call these revelations, accidental and intentional, elements of style.

These revelations tell us as readers what sort of person it is with whom we are spending time. Does the writer sound ignorant or informed, stupid or bright, crooked or honest, humorless or playful-- ? And on and on.

Why should you examine your writing style with the idea of improving it? Do so as a mark of respect for your readers, whatever you're writing. If you scribble your thoughts any which way, your readers will surely feel that you care nothing about them. They will mark you down as an egomaniac or a chowderhead --- or, worse, they will stop reading you.

The most damning revelation you can make about yourself is that you do not know what is interesting and what is not. Don't you yourself like or dislike writers mainly for what they choose to show you or make you think about? Did you ever admire an emptyheaded writer for his or her mastery of the language? No.

So your own winning style must begin with ideas in your head.

1. Find a subject you care about.

Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.

I am not urging you to write a novel, by the way --- although I would not be sorry if you wrote one, provided you genuinely cared about something. A petition to the mayor about a pothole in front of your house or a love letter to the girl next door will do.

2. Do not ramble, though.

I won't ramble on about that.

3. Keep it simple.

As for your use of language: Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. "To be or not to be?" asks Shakespeare's Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story "Eveline" is this one: "She was tired." At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Simplicity of language is not only reputable, but perhaps even sacred. The Bible opens with a sentence well within the writing skills of a lively fourteen-year-old: "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth."

4. Have guts to cut.

It may be that you, too, are capable of making necklaces for Cleopatra, so to speak. But your eloquence should be the servant of the ideas in your head. Your rule might be this: If a sentence, no matter how excellent, does not illuminate your subject in some new and useful way, scratch it out.

5. Sound like yourself.

The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo the speech you heard when a child. English was Conrad's third language, and much that seems piquant in his use of English was no doubt colored by his first language, which was Polish. And lucky indeed is the writer who has grown up in Ireland, for the English spoken there is so amusing and musical. I myself grew up in Indianapolis, where common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench.

In some of the more remote hollows of Appalachia, children still grow up hearing songs and locutions of Elizabethan times. Yes, and many Americans grow up hearing a language other than English, or an English dialect a majority of Americans cannot understand.

All these varieties of speech are beautiful, just as the varieties of butterflies are beautiful. No matter what your first language, you should treasure it all your life. If it happens to not be standard English, and if it shows itself when your write standard English, the result is usually delightful, like a very pretty girl with one eye that is green and one that is blue.

I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most, too, when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am. What alternatives do I have? The one most vehemently recommended by teachers has no doubt been pressed on you, as well: to write like cultivated Englishmen of a century or more ago.

6. Say what you mean.

I used to be exasperated by such teachers, but am no more. I understand now that all those antique essays and stories with which I was to compare my own work were not magnificent for their datedness or foreignness, but for saying precisely what their authors meant them to say. My teachers wished me to write accurately, always selecting the most effective words, and relating the words to one another unambiguously, rigidly, like parts of a machine. The teachers did not want to turn me into an Englishman after all. They hoped that I would become understandable --- and therefore understood. And there went my dream of doing with words what Pablo Picasso did with paint or what any number of jazz idols did with music. If I broke all the rules of punctuation, had words mean whatever I wanted them to mean, and strung them together higgledy-piggledy, I would simply not be understood. So you, too, had better avoid Picasso-style or jazz-style writing, if you have something worth saying and wish to be understood.

Readers want our pages to look very much like pages they have seen before. Why? This is because they themselves have a tough job to do, and they need all the help they can get from us.

7. Pity the readers.

They have to identify thousands of little marks on paper, and make sense of them immediately. They have to read, an art so difficult that most people don't really master it even after having studied it all through grade school and high school --- twelve long years.

So this discussion must finally acknowledge that our stylistic options as writers are neither numerous nor glamorous, since our readers are bound to be such imperfect artists. Our audience requires us to be sympathetic and patient readers, ever willing to simplify and clarify—whereas we would rather soar high above the crowd, singing like nightingales.

That is the bad news. The good news is that we Americans are governed under a unique Constitution, which allows us to write whatever we please without fear of punishment. So the most meaningful aspect of our styles, which is what we choose to write about, is utterly unlimited.

8. For really detailed advice:

For a discussion of literary style in a narrower sense, in a more technical sense, I recommend to your attention The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White. E.B. White is, of course, one of the most admirable literary stylists this country has so far produced.

You should realize, too, that no one would care how well or badly Mr. White expressed himself, if he did not have perfectly enchanting things to say.

In Sum:

Find a subject you care about.

Do not ramble, though.

Keep it simple.

Have guts to cut.

Sound like yourself.

Say what you mean.

Pity the readers.

Thanks for reading The Typewriter's Collage. Connect with me at Twitter/X, Bluesky, Threads, and Instagram at the handle @RealArnieB. I’m on LinkedIn and Facebook under my real name. Plus, check out my newly-redesigned and updated website, www.arniebernstein.com.

Useful Links:

More on Vonnegut at Kurt Vonnegut Library and Museum.

Here’s the complete 1980 ad campaign for International Paper.

Joel L. Miller’s excellent Substack “Miller’s Book Review” on Why Slaughterhouse-Five Still Matters

My review of The Writer's Crusade: Kurt Vonnegut and the Many Lives of Slaughterhouse-Five by Tom Rosten for The New York Journal of Books

What’s your favorite writing advice from your favorite author? Do you agree with Vonnegut’s wisdom or do you think it’s all stuff and nonsense? And so on. That’s what the comment section is for.

And just because you made it this far, here’s your bonus content: Kurt Vonnegut’s cameo appearance in the 1986 Rodney Dangerfield comedy Back to School.

That was some wonderful writing!