Three Dangerous Tipping Points for Writers, Part II: The WGA Strike and The Hollywood Powers That Be

Sure, Hollywood is full of sharks who see script writers as nothing more than chum. But remember, "Jaws" ended with its villain blown to smithereens.

But first, a brief addendum cum introduction

One of my readers pointed out that scriptwriters are story tellers and not “content creators,” as I refer to WGA members in this piece. That was a deliberate choice on my part and not meant to slight my hardworking peers in the WGA. At first I debated between using "storytellers" versus "content creators." Ultimately I went with the latter, since what studios want is want content, not stories. Content, content, and more content is how they make their considerable scratch. They don't give a crap about "story," no matter how many times they say they do.

And, now on with the main attraction

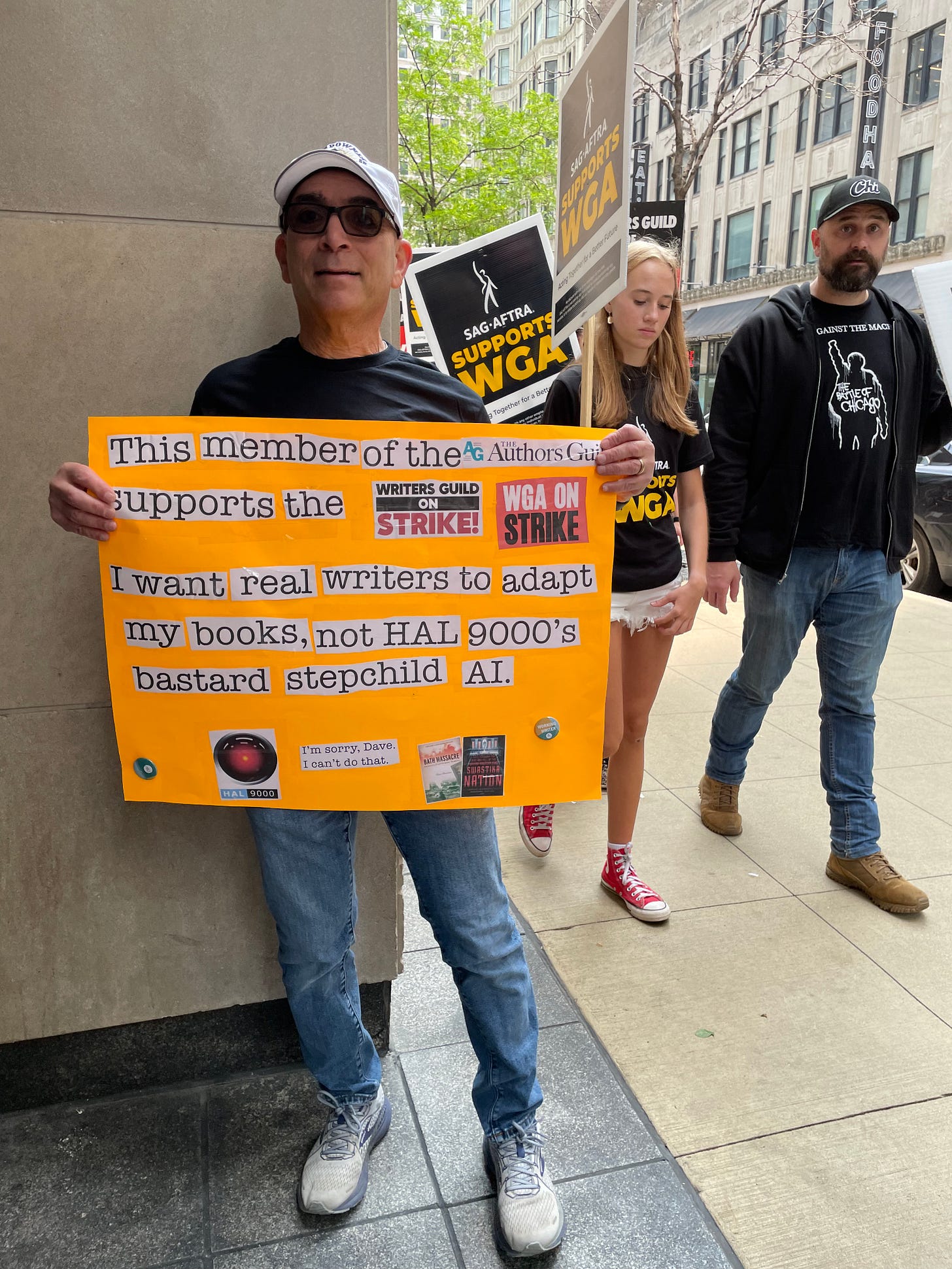

If you’re familiar with the ongoing writers strike in Hollywood, feel free to jump to the next paragraph. But for everyone else, here’s a quick summation of what’s happening. On July 14, 2023 members of the Writers Guild of America (WGA), the union representing film and television writers, went on strike. I hesitate to use the word “strike,” other than it makes for handy designation for what’s going on between WGA members and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). AMPTP, the entity responsible for negotiating contracts with professionals in the entertainment industry, refuse to come to the bargaining table. That’s not a labor strike. It’s AMPTP’s strategy to destroy the WGA. (Another strike between AMPTP and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists—aka SAG-AFTRA—is a separate labor action with similar issues. As I’m concentrating on writers, I’m tabling that part of the story. You can find of plenty of good information elsewhere regarding the SAG-AFTRA strike.)

AMPTP speaks for studio executives, those Powers That Be (PTB) awash in dump truck loads of money. It’s no secret that a lot of Hollywood PTBs make huge multi-multi-million dollar base salaries, fattened up with signing bonuses, productivity incentives, and stock options. Add to that the many tax dodges and workarounds PTBs use to keep their accountants busy. A successful PTB can accumulate more money in six months than most of us will see over the course of our lifetimes. Even mid-level PTBs can buy all the toys they want, like mansions, yachts, Maybach automobiles, private island villas, and maybe a bottle or two or three or more of Johnny Walker and Sons Diamond Jubilee Blended Malt Scotch Whiskey. (Check out those prices. Yowzah!)

There’s a lot of dough to be made providing entertainment for movie theaters, network television, cable, and streaming services, plus sales of Blu-ray discs and digital downloads. Yes, the PTB sure have it made. But you know who’s not getting all those fancy yachts and Cuban cigars, let alone a living wage?

The people who create those movies and shows. Writers.

In the beginning there were the words—and the words came from writers

You can’t have a movie or television show without a script (documentaries and reality television being notable exceptions). There was a time when writers got some respect in Hollywood: during the 1930s and 1940s the PTBs hired the best talents they could find to pen screenplays. Literary darlings and stellar playwrights filled out the rollcall, including Dorothy Parker, George S. Kaufman, Ben Hecht, Christopher Isherwood, Clifford Odets James Agee, William Faulkner, and even Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World (his screenplays included Pride and Prejudice [1940], Jane Eyre [1943], and in an unlikely nod to Huxley’s interest in hallucinogens, some uncredited work on Walt Disney’s sanitized 1951 version of Alice in Wonderland).

Other prominent screenwriters who became well-known as masters of the craft were Herman J. Mankiewicz and Dalton Trumbo. Their legacy as Hollywood screenwriters who bucked the system looms large. Years after their respective deaths, both men were subjects of biopics which used their instantly-recognizable names for the titles: Mank and Trumbo.

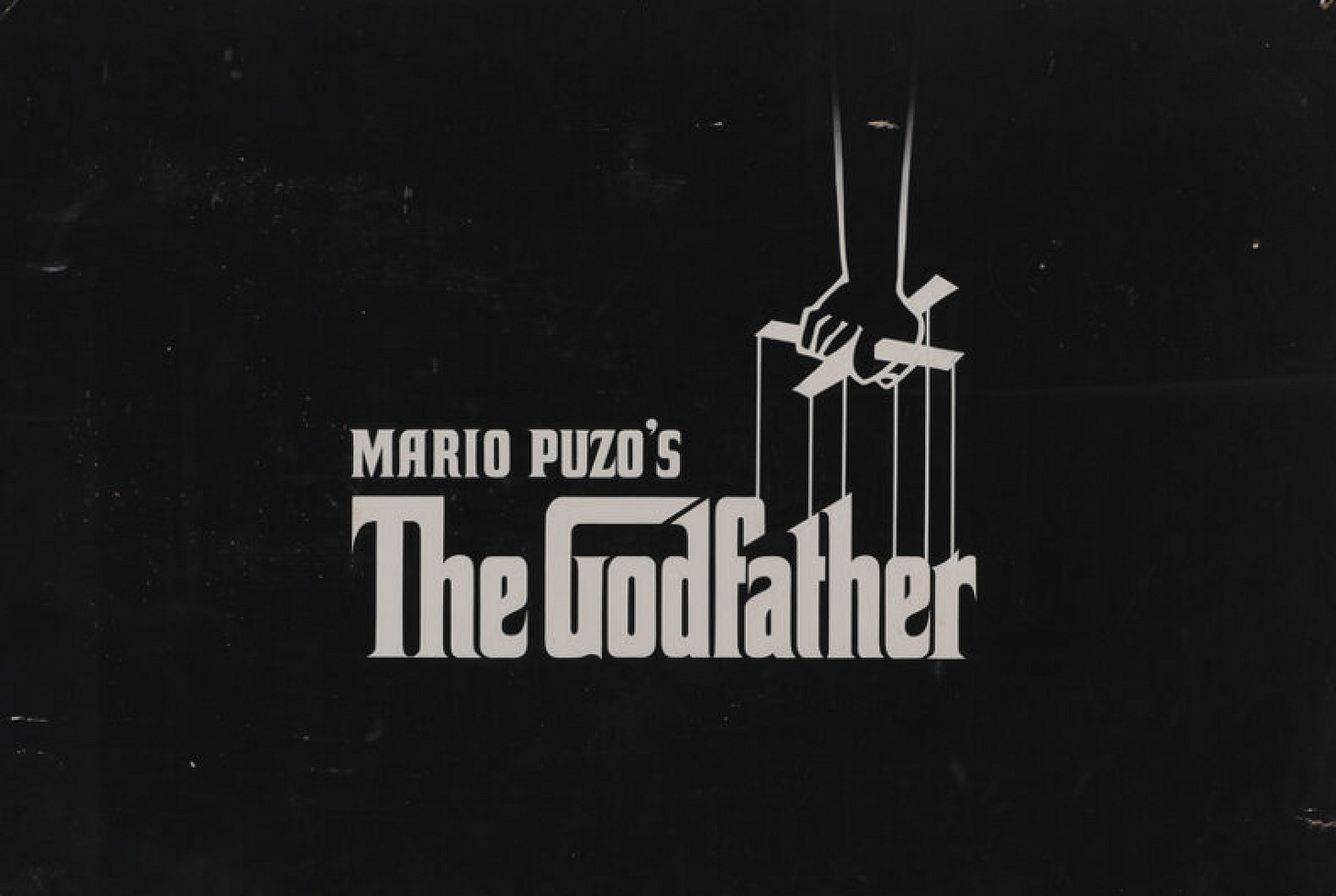

Some screenwriters were revered enough to have their names directly connected within the film itself. The opening title of Network (1976) is followed with the credit “by Paddy Chayefsky.” The opening title of The Godfather (1972) reads “Mario Puzo’s The Godfather.” Puzo authored the mega-popular bestseller which became the film he co-wrote with director Francis Ford Coppola. Lines that have become part of our cultural DNA—quotables like “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse” and “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes”—all have their genesis in Puzo’s 1969 novel.

Giving writers this kind of credit is memorable because it is so rare. Sure, there plenty of screenwriters revered over the years for their talents: Paul Schrader, William Goldman, Robert Towne, Spike Lee, Nora Ephron, Aaron Sorkin, David Mamet, Joel and Ethan Coen, Quentin Tarantino, Nancy Meyers, the Wachowskis. Many of them also directed their scripts. But the vast majority of writers aren’t widely known outside of the entertainment industry. For every William Goldman or Aaron Sorkin, there is a vast ocean of people trying to make a living doing what they do best: write.

Making it big in Hollywood is not always a matter of talent, although that certainly doesn’t hurt. But talent alone doesn’t guarantee a writer will sell scripts that get produced. Some people get lucky. Some don’t. There are myriads of gifted writers who never got the break they needed, didn’t have the right connections, or any one of a thousand more reasons. Hollywood is a rough business. I know a lot of talented scribes who went to California and turned up empty. Remember Sunset Boulevard (1950), the sardonic black comedy starring William Holden as the almost-made-it-but-just-didn’t-get-there screenwriter Joe Gillis. There’s a reason writers love that film. Still, if being a Hollywood screen or television writer is your dream—well, why not try?

WGA members work in many disciplines: dramatic series and sitcoms for broadcast, cable, and streaming services, film, late night comedy, cartoons, game shows, Hallmark Christmas movies, and even datetime yak shows like The View. Pardon the unintentional pun, but in other words just about everything you watch begins with WGA members.

This isn’t the first time the WGA has gone on strike: here’s a good overview of the previous walkouts. There is a common thread to these actions: fair pay for writers when it comes to residuals from television reruns, feature films broadcast on television and cable, home video sales, and work distributed via the internet.

This strike it’s different...very different. A series or movie on Netflix, Hulu, Apple TV, or other streaming services is not like something being rerun on a cable channel or offered for sale as a Blu-ray disc. Those revenues were negotiated under previous contracts between AMPTP and WGA. But a lot has changed since the last strike, which lasted for 93 days from November 5, 2007, to February 12, 2008. In the process, how writers get paid has changed and for the worse. The current strike began on May 2, 2023, with no end in sight. PTB has made no effort to negotiate. They just put an offer on the table, one that is wholly unacceptable to WGA members, and said “take it or leave it.” WGA went with the latter. Consider these stories emerging from the WGA picket lines:

The Bear and the barely paid

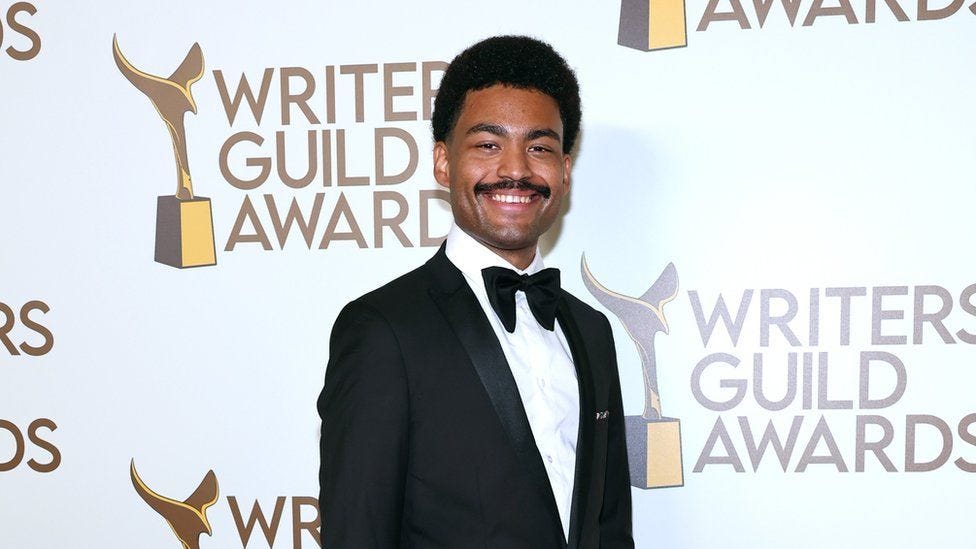

Alex O’Keefe made the switch to television after working as an organizer with President Obama, being a force in the Green New Deal movement, and a speechwriter for Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey. He switched to scriptwriting and quickly a landed a dream job, joining the writing staff for The Bear, that FX/Hulu series you love about the trials and tribulations of workers at a Chicago beef sandwich joint. O’Keefe’s scripts were quality material, but real job conditions for writers on the show were a whole lot worse than the fictionalized employment of those sandwich jockeys on The Bear.

O’Keefe worked out of his Brooklyn apartment because of Covid. When the pandemic restrictions were lifted, producers maintained a Zoom meeting room rather than bring O’Keefe out to Hollywood. Actually, O’Keefe didn’t work out his apartment. His salary for The Bear covered his rent and not much else. When O’Keefe’s space heater broke down, he couldn’t afford to replace it. Rather than write with mittens on his hands, O’Keefe took his laptop to his local public library. He spent hours there, creating all sorts of chaos and comedy for Carmy, Richie, Sydney, and the rest of the gang. Free library Wi-Fi allowed O’Keefe to send his finished scripts from the cold confines of Brooklyn to the sunny climes of his bosses in L.A.

The Bear is a bona fide hit, often praised for its witty writing. It brings in a lot of revenue for its producers and Hulu/FX, a division of the mighty Disney empire. But O’Keefe? He wasn’t getting much scratch in return. The Bear won top honors for comedy series writing this past March at the WGA’s annual awards show. That night, as he joined his fellow writers on stage to much applause and congratulations, all O’Keefe could think about was his bank account, which had a negative balance. He even had to borrow money so he could buy a tie to wear at the ceremony.

O’Keefe could have made more bread—the green and silver kind—working for a Chicago beef sandwich shop then he did in his nine weeks as a staff writer on a hit series. A lot of people were making a lot of money off The Bear, save for its writers. O’Keefe was living the dream, but his reality was a nightmare. The strike has reenergized his political animal within. O’Keefe is turning his experience on The Bear into a full-powered campaign against the PTB.

Comedy writers? The joke is on them.

From its earliest days television relied on sketch comedy to draw in audiences. Quick scenes, fast gags, hit ‘em in the gut punchlines. It’s a genre that began in1948 with The Texico Star Theater, the show that launched Milton Berle’s career. What followed in the ensuing decades is an impressive list of talent and shows: The Colgate Comedy Hour with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, The Jackie Gleason Show, The Ernie Kovacs Show, Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, The Flip Wilson Show, The Carol Burnett Show Van Dyke & Company, In Living Color, and the NBC warhorse Saturday Night Live. The impact of SNL spawned imitations like Fridays and even the most unlikely of all sketch comedy shows Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell.

The most legendary of all are the three shows hosted by Sid Caesar in the 1950s. His Admiral Broadway Review begat Your Show of Shows begat Caesar’s Hour. By any standard Caesar remains one of America’s most brilliant and influential television comedians, and in no small part because of his writers. Consider all these talents Caesar threw together: Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Mel Tolkin, brothers Neil and Danny Simon, Larry Gelbart, Woody Allen, Selma Diamond, Joseph Stein, Howard Morris, and many others batting around sketches and punchlines.

The writing room for Caesar’s Hour was an incubator for genius comedy writing. You can’t think of late 20th century entertainment without any of those talents. Caesar’s team became entertainment titans. Consider their post-Caesar works. Movies like Annie Hall and Oh God!, television’s The Dick Van Dyke Show, Get Smart, All in the Family, M*A*S*H, Broadway’s Bye Bye Birdie, Fiddler on the Roof, and the entire Neil Simon canon. When Mel Brooks was developing the script for his riotous comedy Blazing Saddles, he put together a team that worked like an old Sid Caesar writing room, bouncing jokes and gags off each other to create the final script for this masterpiece of movie anarchy.

AMPTP wants to 86 all that. Rather than develop talent via writers rooms and mentoring, they want comedy sketch writers to work on a day-by-day basis. Essentially, what they’ve put on the table would turn the slam-bang world of comedy writing into a business model akin to the rideshare services Uber and Lyft. In the contract proposal offered PTB, writers get paid by the sketch. If you’re good, you get called back the next day. If your joke misfires…well, no second chances. Plus there’s no guarantee a sketch will make it into the show, which affects both a comedy writer’s career path and bank account.

As you’d expect, comedy writers have rebelled as only they can using every satirical tool in their joke bags to rip into the PTB. Check out their Contract TK channel on YouTube.

The Incredible Shrinking Writers Rooms

As long as we’re on the subject of writers rooms, consider how these too are being decimated by the PTB. Writers rooms have been downsized to what’s now called “mini rooms.” Back in the days when broadcast television was your only choice for home entertainment, the average number of shows for dramas and sitcoms was between 24 to 28 episodes. A typical television season ran from Labor Day through Memorial Day; shows might be shelved for a week so that the network could broadcast a “special” (think Bob Hope and Christmas). Reruns were reruns, not “encore broadcasts.” Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, popular shows went on hiatus with summer replacement shows taking their place. (Does anyone remember the 1977 summer comedy/variety series The Starland Vocal Band Show? Yes, kids, this really was on national TV.)

Flash forward to 2023. With the expansion of cable and streaming, a series season can run for as little as nine episodes. Viewers binge their favorite shows anytime they want with just a punch of the remote button. Two of Netflix’s biggest hits seem like their seasons are over before they even started. Emily in Paris has 10 episodes in each of its three seasons. Stranger Things has three seasons with eight episodes and two with nine episodes. Apple TV’s Schmiagdoon! clocked in at six episodes for each of its two seasons. Even with an hour running time and the considerable production costs that go into these shows, smaller episode runs and shorter story arcs means that scripts need to get pumped out and fast. Writers could work on a hit series, but when the job is done, they’re left struggling. Keep in mind, part of a writer’s salary goes to agents and pays for income taxes. What’s left at the bottom line is lot less than the contracted salary would appear to be. Alex O’Keefe’s situation is the new abnormal normal. With the rise of mini rooms comes the fall of WGA members income.

PTB: The Robber Barons of 2023

Like everyone else in the world, writers have to eat and pay their bills. Too many WGA members are living paycheck to paycheck. And when you’re on strike, things can get dire if you need to dip into a savings account or other nest egg. Or you could be in the same situation as Alex O’Keefe. A lot of people in the film business fit that category.

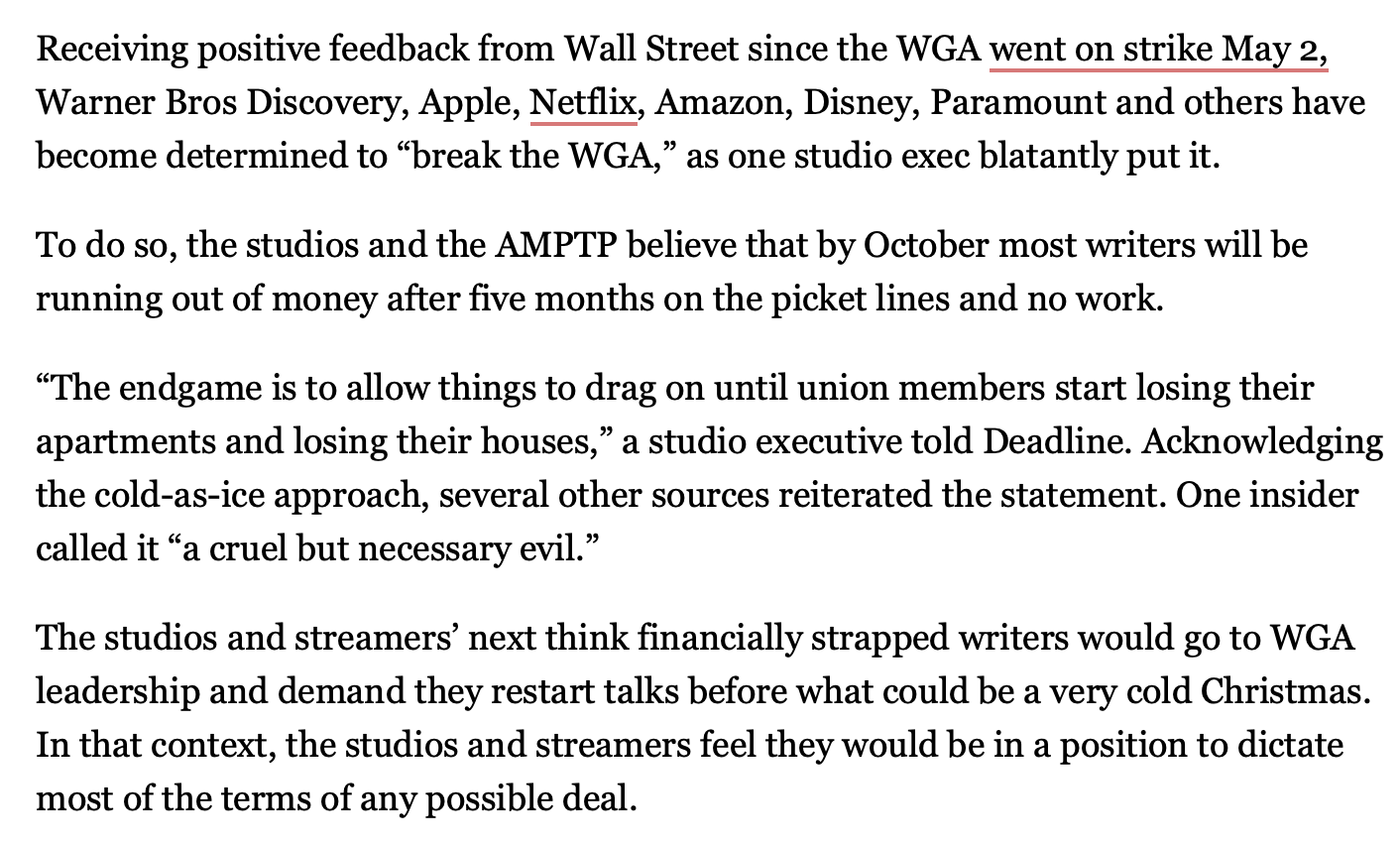

And what do BTPs think of this income inequality? One unidentified executive told the entertainment industry blog Deadline that AMPTP’s intent is to break the striking writers into submission:

A spokesperson for AMPTP refutes the unnamed BTB, stating “These anonymous people are not speaking on behalf of the AMPTP or member companies, who are committed to reaching a deal and getting our industry back to work.”

You might believe this spokesperson. But then again, PTBs aren’t exactly the most honest of people. Remember Forest Gump? A monster-huge feel-good hit. Cost to make: $55 million. Worldwide box office gross: $678 million. That doesn’t include home video sales, broadcast rights, or other income earned by the film. Yet the BTB tried to cheat Winston Groom, author of the novel that was the basis for Forest Gump, out of millions of dollars. Despite the incredible return on that $55 million investment, PTB claimed that the film adaptation of Winston’s book was a big money loser, hence they owned him nothing. As Chico Marx said to Margaret Dumont in Duck Soup: “Well, who you gonna believe? Me or your own eyes?”

For these reasons and so many more, WGA is fighting the good fight. If producers think they can break the WGA, they’re wrong. Remember, it’s not the PTB who create film scripts: it’s the writers. Unlike someone shoveling dump truck loads of money into another yacht, WGA members have an insider’s knowledge of the story that the PTB just don’t understand. Who controls how a scenario comes to an end? Writers. The underdog good guys always win. The obscenely rich villains always lose. Fade to black. The end. Audience exits the theater delighted that this story has a happy ending.

Links:

WGA’s Strike Info Website, including their response to AMPTP response

Next time: Artificial Intelligence: the existential threat posed by HAL 9000’s great grandchild.

Are you a WGA member and/or supporter? Maybe your a PTB (boo! hiss!) Share your thoughts in the comment section or on my Twitter (okay, X) feed @realarnieb. And check out my website www.arniebernstein.com