Charlie Chaplin: The End of Silence. The Appeal in Passion

Two interpretations of Charlie Chaplin’s transitional films between the silent era and talking pictures.

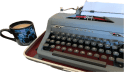

Modern Times (1936)

The silent film era effectively ended in 1927 with The Jazz Singer. Al Jolson both astounded and delighted audiences when he spoke—spoke out loud in a movie!—“Wait a minute, wait a minute. You ain’t heard nothing yet!” From there Jolson launched into a lively rendition of the pop hit “Toot, Toot Tootsie, Goodbye.” An appropriate choice for this revolutionary turn by Warner Brothers studios. The Jazz Singer was, in a sense, a “goodbye” to the era of silent movies. “Jolson sings!” cried the ads. The rest of Hollywood got on board with the new technology. Everyone but Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin is synonymous with the silents. Even in 2024, nearly 100 years into the sound era, people who’ve never seen a silent film instantly recognize Chaplin’s character of The Little Tramp—and know that he represents a bygone era.

Chaplin’s enduring legacy is simple: he was the first true popular artist of the 20th century, blessed with a keen understanding of what the public wanted. It made him one of the wealthiest men in the world, which meant that as long as he funded his own pictures, Chaplin could continue making them the way he wanted: silent.

But this could only last for so long. By 1936 it was clear the public taste for silent films was gone. Chaplin had to acquiesce. His answer was Modern Times, an unabashed satire on the machine age. The majority of the film relies on the familiar silent movie grammar Chaplin honed during the 1910s and 1920s: pantomime, music, and intertitles in place of spoken dialog. Vocals belong only heartless factory bosses, barking out orders via telescreens to their hapless employees; or background murmuring within crowd scenes.

Still, Chaplin had to give in. The modern times (if you will) of 1936 demanded change. The Little Tramp had to speak.

In the closing minutes of the film, The Little Tramp takes a job as a singing waiter. He writes lyrics on the cuffs of his shirt so as not to forget them, heads onto the café floor, and begins to dance. The Tramp flings his arms out wide, unknowingly catapulting his cuffs from his shirtsleeves into the dinner crowd. When it’s time to sing, he consults his “cheat sheets,” only to find they are missing. The Tramp looks helplessly offstage to his partner, played by Paulette Goddard (Chaplin’s real life paramour at the time). He doesn’t know what to do. She mimes her response, followed by the intertitle: “Sing!! Never mind the words.”

Silence is the essence of The Tramp. We understand him because he doesn’t talk on screen. Twenty-two years after his debut in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914) the sound era now demands that this iconic character face his ultimate challenge. The Tramp will at last speak.

What happens next reflects Chaplin’s genius for subtlety. The Tramp uses nonsense words in a song about flirtatious young lovers. Graceful movements and facial gestures convey the story. Words are almost secondary. It’s a wonderful scene, one of Chaplin’s best.

It's also one of the most poignant moments in all of film history. Chaplin has given in to modern times. The Tramp speaks. The silent era is over.

It breaks my heart every time I watch it.

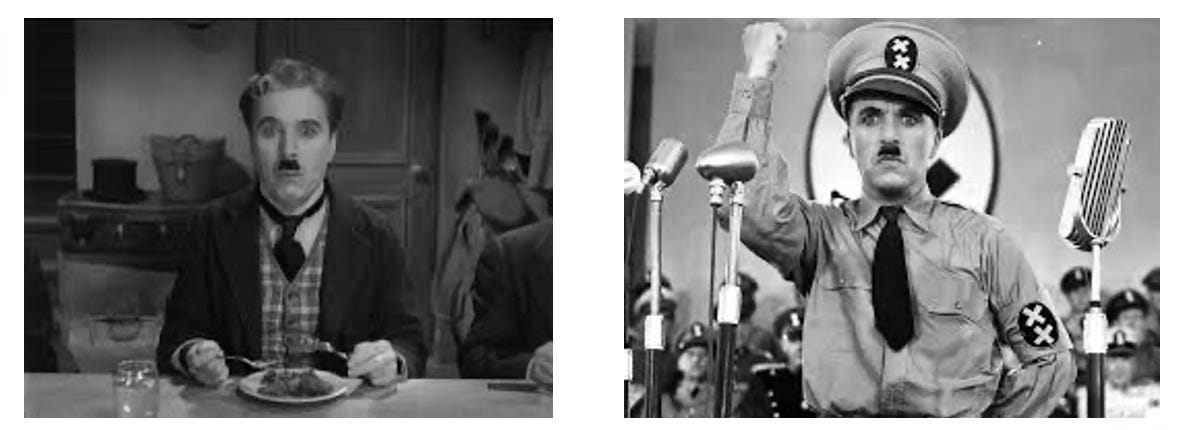

The Great Dictator (1940)

The story goes that in the late 1930s Chaplin was often approached by friends with the same observation: “You know, Charlie, you and Hitler wear that same mustache. Maybe you can do something with that.”

Chaplin, the beloved humanitarian. Hitler, the epitome of evil. Ironically, born days apart in 1889—Chaplin on April 16 and Hitler on April 20 (also my birthday, which I’ve written about in a previous Substack). It was inspiration waiting to happen. Chaplin grabbed this opportunity by its metaphorical throat.

He studied documentary footage of Hitler, all word spewing and wild gesticulations. According to his close confident Tim Durant, Chaplin had a sly smile as he watched the German führer in action. “Oh, you bastard, you son-of-a-bitch swine,” Chaplin sneered. “I know what’s in your mind.” Adolf Hitler was pomposity ready-made for lampooning. Chaplin had his next film.

In The Great Dictator Chaplin played a dual role of the oppressed and the oppressor. First there is a modified version of his Tramp character, now a nameless Jewish barber living in ghetto community. On the other end is the great dictator himself, Adenoid Hynkel, the Phooey of Tomania. Those parody names aren’t subtle nor particularly funny, but that's not the point. Hitler was deserving of this lowbrow mocking.

Through a series of mix-ups at the film’s end the barber is mistaken for the dictator. He must now speak at a massive gathering, akin to Hitler’s address at the 1934 Nuremberg rally. The barber’s speech is preceded in an affirmation of fascist rule by Chaplin’s stand-in for Joseph Goebbels, Herr Garbitsch (sounds like “garbage”), Hynkel’s Minister of Propaganda, played with cold efficiency by Henry Daniell.

The barber sits on the speaker’s platform with Commander Schultz (Reginald Gardner), a turncoat against the Tomanian dictatorship. “I can't speak,” the barber tells Schultz. “You must,” is Schultz’s reply. “It’s our only hope.” The barber repeats the final word. “Hope.” He takes his place at the podium. He steps in front of the microphone to address the rally and millions of radio listeners. And he speaks.

What happens next was the subject of considerable debate after The Great Dictator’s release in 1940, a debate that continues to this day. The barber delivers a fiery address, decrying fascism and extolling the inherent goodness of man. It was derided by many, with the consensus being that Chaplin turned the barber into a self-important extension of the filmmaker. It didn’t fit the movie. It was Chaplin at his most pretentious.

Wrong, says I. This was the right speech for the right time, a cry for decency when homicidal madness was engulfing Europe. Would the little barber have been capable of delivering such a forceful oratory? Absolutely not. That’s not the point.

Watch Chaplin just before he begins to speak. What happens is so subtle that you won't see it if you don't know it's there. It took me many viewings of the film before I discovered it myself.

The little barber takes his place at the microphone. He makes a slight change in his posture, a tiny shrug as if Chaplin the actor is discarding his costume. That’s exactly what is happening. He is an actor dropping character. He is no longer the little barber. He is Charles Spencer Chaplin appealing to the world to stand up to Hitler, to stand up to fascism. “The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed, the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress,” Chaplin says, looking right into the camera. “The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish”

And then, when he’s done, Chaplin steps back from the mic. His physical demeanor changes. The costume is put back on. Once again he is the little barber. Chaplin has said what the world needed to hear, even now as then.

Next week, two more interpretations: Quentin Tarantino goes to Heaven, plus it’s time to send the old TV warhorse to the glue factory.

Some related links:

Thanks for reading The Typewriter's Collage. Share your thoughts in the comment section or on my various social media, all of which are linked on my website: www.arniebernstein.com.

Brilliantly observed and written. Just as subtle as Chaplain's performance. Write On Arnie.

Wonderful piece.

If I may, here's a piece I wrote on the emotional impact of sound/color films versus silent/b&w: https://graboyes.substack.com/p/that-the-past-shall-not-grow-old. This was an analysis of Peter Jackson's decision to add sound, color, and AI-generated frames to WWI film, freeing the soldiers from what he called, their "Charlie Chaplin world.” Jackson noted the impropriety of colorizing films where directors deliberately chose black-and-white over color film" (e.g., 2011's "The Artist"), and I added, "Perhaps Charlie Chaplin, too, would have used color film, had it been available. But it would still be abominable to colorize 'The Little Tramp' today. Chaplin forged his art with the materials of his time. Michelangelo didn’t have access to acrylic paint, but that’s no excuse for colorizing 'David.'”